Podcast: Download (Duration: 56:23 — 45.4MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | TuneIn | RSS | More

How can we write about places that inspire us in an authentic way even when they are not our own country? Tony Park gives his tips for writing setting, and also outlines how his publishing experience has changed over the last two decades.

In the intro, KDP printing costs are changing from 20 June; plus, join me for AI for Writers online webinars.

This podcast is sponsored by Kobo Writing Life, which helps authors self-publish and reach readers in global markets through the Kobo eco-system. You can also subscribe to the Kobo Writing Life podcast for interviews with successful indie authors.

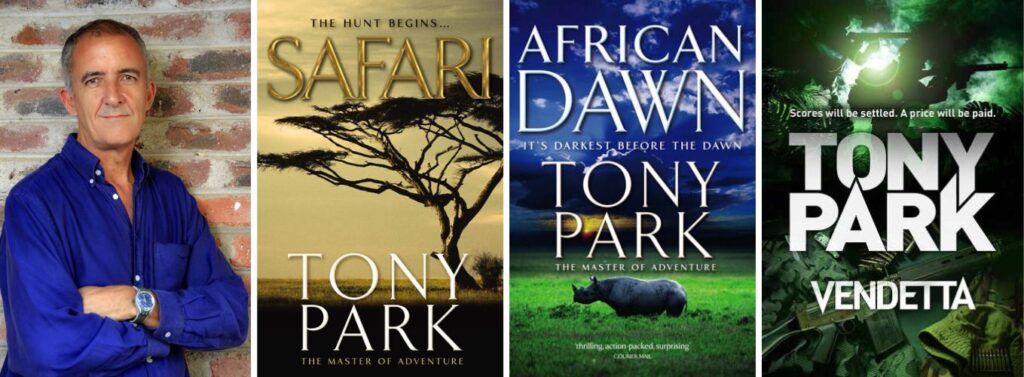

Tony Park is the author of 20 thriller novels set in Africa, as well as the co-writer of several biographies.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- How Tony’s publishing experience has changed over two decades

- Splitting territories when licensing your rights and tips for rights reversion

- Tips for writing setting and how it incorporates into all aspects of your book

- Research and avoiding stereotypes

- Writing outside of your own country and personal experience

- Balancing writing a compelling story with advocating for a cause (without lecturing)

You can find Tony at TonyPark.net

Transcript of Interview with Tony Park

Joanna: Tony Park is the author of 20 thriller novels set in Africa, as well as the co-writer of several biographies. So welcome, Tony.

Tony: Oh, Joanna, thank you so much for having me on the podcast. I really appreciate it. I’m a huge fan.

Joanna: Thank you so much. First off—

Tell us a bit more about you and how you got into writing.

Tony: Look, it might sound a bit cliche, but it’s absolutely true, that the only thing I ever wanted to do in life, from the time I was a little boy growing up in Sydney, in Australia, was to write a book.

My family weren’t particularly well off, and my mum was working two jobs and used to leave us in the library after school. I just thought, wouldn’t it be cool if this could be your job to write books. Of course, as we all know, listening to this podcast, it’s not like you can wake up one day and say, okay, I’m going to write a book, and publish it, and away we go.

I loved writing as a kid. I wasn’t any good at English or maths at school, and so I pinned my hopes on writing. After I left school, I got a job working in local newspapers, and that cemented my love of writing. Then I just tried and tried and tried. I had a number of false starts over the years as my life progressed. I’d wake up early in the morning before work and try and start a novel. And I’d try after work, and I couldn’t really focus.

This went on for years and years. Too long, I think I waited too long to get serious about it. I got married, and got a mortgage, and real life intruded and everything.

The two biggest challenges I faced were time, right, that everybody faces, you know. But a place was what eluded me, and I know we’re going to talk about that a bit later on.

All I knew is I wanted to write a novel. I hadn’t even really thought long enough to think where I was going to set it or when I was going to set it. When I was about 32, 33, I went to my wife and I said, “I’ve got an idea. How about I leave work and you support us for six months, and I’ll try and write a book?”

Joanna: Nice one!

Tony: And to my utter astonishment, she said, “Yes, go for it,” because I think she was sick of me, you know, going on about how much I wanted to write. And so I did.

I left work, and I wrote a book. I bought a couple of books about how to write books. I wrote this book like textbook style, like I plotted it meticulously, I had character profiles, and a timeline, and chapter breakdown and everything.

The place I picked for it was wrong because I made a fundamental error.

I was writing a book that I think I wanted other people to read, rather than something I was passionate about.

So I set it in the Australian Outback. And there was one tiny problem, I’ve never actually been to The Outback.

Joanna: Even though you’re Australian.

Tony: Even though I’m Australian. I’m a city boy, you know, I was living in the suburbs.

I took six months, I wrote a book, and I failed spectacularly. I didn’t enjoy the process of plotting. I didn’t know that you could not plot, that you could just make it up as you went along because I had no formal training. And I found it very mechanical and very boring.

[More on discovery writing here!]

Around about that time, my wife and I went on a holiday to Africa, which was supposed to be a once-in-a-lifetime trip. Instead, we got hooked on Africa and went back the following year, and back the following year.

On my third trip to Africa, we had a long trip, about four months around Southern Africa, and I had another go at writing a book because I once more had time. I’d had to go back to work, but I once more had time. And here I was in a place that I had kind of started to get to know, and was amazing and inspirational and fascinating, and there was so much going on here.

I thought, I could write a book set in Africa. And instead of plotting it, I’ll just make it up as I go along. So it was set on a fictitious tour around Africa, as my wife and I were travelling around Southern Africa. Each day as we moved camp, I just wrote another few pages and made it up as we went along, and just copied the landscapes that we were in into the text.

I sent it to a publisher, and the first publisher I sent it to, Pan Macmillan Australia, published it. And my publisher said you can write the books in Africa. And here I am 20 years later writing the books in Africa.

Joanna: I love the story. There’s so much to learn from that. So 20 years later, and we’re going to come back to Africa and the setting thing, but you said 20 years later, you’re still writing and publishing. But of course, things have changed in 20 years. One of the things I picked up from your website is that you also run Ingwe Publishing.

Tell us how your publishing experience has changed over the last two decades?

Because things have really changed and you have too, obviously.

Tony: It’s massive the amount of change. Yeah, my life has changed, it has moved on.

Technology has changed. Everything has moved on. And I think like, you know, when we talk about those days, it seems like a long time ago, is that people would pin their hopes on getting a commercial publishing deal. And I did, and I was absolutely thrilled and over the moon when I got it.

A funny little side story, I was in the Australian Army Reserve for 34 years. I was actually in Afghanistan. I was deployed there in 2002 when I got the email from my publisher saying, “Hey, good news. Open this email, we’re going to give you a publishing contract.” And I couldn’t even have a beer to celebrate because we were on the dry out there.

So I was really thrilled to get a publishing deal. I thought that was the be all and end all. And over the years, I had some limited success, it started to grow.

My primary market was my home market in Australia, even though these books are all set in Africa. It is a thing, it’s almost like a genre of its own, African fiction. I had some success getting commercial publishing deals in the UK, and later in the US, but the books didn’t do particularly well.

I had gone from this high to thinking, “Oh, no, why aren’t I selling many books there?” And that really started to affect me quite badly. Then things changed dramatically, you know, over the last few years, and I learned so much. Not least of all from your podcasts and hearing from other authors who were independently publishing.

Of course, 20 years ago, when I was first publishing, there was quite a bit of stigma attached to self-publishing. You know, it was called vanity publishing, because you had to be very vain, and you had to be very rich to do it. You’d have to print thousands of copies of books, and then pay a distributor to try and get them in the shop. So it was this hugely involved, expensive process.

I have found in more recent years, that what made more sense for me was to kind of do a civil sort of deal with my UK publishers and the distributors and say, “Look, guys, it’s not really working for both of us,” because it wasn’t.

I was losing so much, because I had an agent at the time, I was losing so much on all of the in-between cuts that come out of a royalty. It wasn’t worth it.

I was down to about 30 pence per book, I think I was making, you know.

So I set up Ingwe Publishing, Ingwe means leopard, and took back my rights. I was then able to start exploring print on demand and eBook self-publishing, and indie publishing.

And I found that for my sales in the UK and US, which I’m very proud of, but you know, I’m not selling hundreds of thousands, or millions of books, I make a really, really good second income out of it.

I think having your own imprint and taking control of those matters, not just from a business side of things, but from a personal side of things, has been really rewarding and fulfilling, far more so than chasing those kinds of overseas publishing deals and trying to define yourself by those sorts of deals. Which they quite often aren’t really in the interest of an author.

Joanna: So you’re, I guess, what we now call a hybrid author, in that you still license to traditional publishing in Australia?

Tony: And South Africa. Australia, New Zealand and South Africa are my commercial markets, or traditional markets. Yeah.

Joanna: Okay, that’s really interesting. And so just for people listening, that’s English language that you have split into territory.

So you’re not signing contracts for World English, you’re splitting the territories.

Tony: Absolutely. And I made so many mistakes when I started out.

Like I was so pathetically grateful to my publisher, and I still am, you know, but I had to look at this now as a business. I wouldn’t say I didn’t read my contracts, I didn’t really understand them that well, maybe.

But yeah, I was willy-nilly signing over English language rights worldwide. I then had to go back to my publisher and say, “Look, I’m going to start doing my own thing. So I need you to please give me back all those worldwide rights.”

The same thing went for audio. I’ve been really interested to hear you talk about changes in the audiobook world. I have a good relationship with an audiobook publisher, with Bolinda, in Australia. And I now keep my audio rights to myself, and I do with them what I want to.

I think too many authors that chase that commercial publishing deal are so grateful, that they think I’ll do whatever you want to, you know, I will give you anything that you possibly ask for. And of course, that doesn’t make sense.

So yeah, I’m a hybrid, I guess is the best way to talk about it. I really enjoy doing my own thing. Of course, it is such an amazing, constantly changing environment that we live and work in. It puts a lot of onus on authors to stay on top of that, but I enjoy it. I enjoy kind of the buzz of the business side of it.

Joanna: I think that’s a good tip as well. I mean, you do have to enjoy the business side. I think you can learn how to enjoy it. I mean, like you said, you didn’t start out that way, you just learned it over time. That’s important

Just a question on the process of getting your rights back. So there’ll be people listening who have signed those contracts, maybe a while back, or even more recently, and now they’re like, oh, dear, I shouldn’t have signed that.

Give us a few tips on the process of getting rights back.

Tony: Yeah, well, I think if you have a good relationship with your publisher that certainly helps. And I was lucky, I always had a good friendly relationship. I never at any stage got the feeling that they were ever trying to rip me off or pull one over on me or anything like that.

It was more a matter of saying to them, “Look, I signed over all my English language rights. You had a go at getting me some foreign translations deals or foreign publishing deals, maybe a UK deal because I was based in Australia, and it didn’t work. I would like to take those back.” I didn’t have any resistance for that.

Certainly, when there’s no money involved, there’s no resistance. In the case of one of my earlier books, Pan Macmillan Australia got me a publishing deal with Pan Macmillan UK. That book was in print for a year or two and didn’t do particularly well. They didn’t want any more of the books. So then when I said, “Can I have all my English language rights back?” they didn’t really have a leg to stand on. They had tried to get me a UK deal, it didn’t work.

So I had to do it in writing, it’s quite an involved process. I’ve got to do it in writing, and then the rights people within the publishing house have to do an amendment and send that back to you to sign.

Where there’s money involved, I’m also looking at taking back some rights from the UK from a publisher that still distributes into South Africa, which is one of the deals I did in the past. And if I want those rights back for South Africa, I’ll have to pay for those. They will calculate that based on my annual sales and any advances that are still outstanding.

In my personal experience, if there’s not really any serious money involved in it, publishers are very reasonable on this kind of thing.

Joanna: Yes, it’s interesting, isn’t it, that paying for things. I actually recently paid out an audiobook narrator in order to get the rights back for an audiobook. I mean, it’s funny, because when we sign these things originally, we have a certain thing in mind, then years later, we’re like, okay, I’ve changed my mind. That’s fine. So it’s good to know, and people listening, you can go back and renegotiate contracts. That is part of it.

As you say, trying to be less emotional is probably the best idea. Like whose business interest is it in and try and think about it from the publisher’s perspective as well.

Try to come to a business arrangement, not an emotional thing. It’s good to know, or at least be interested enough, to read about copyright and how these contracts work. It’s kind of fun once you once you get into it. It’s really interesting.

Let’s return to Africa. So hopefully people can hear from your accent that you are Australian, and obviously you mentioned it before. But your books are set in Africa, and you live between Sydney and South Africa.

So tell us a bit more about the books and how you weave in your fascination with Africa and how you write setting when you’re not from this country. You set it in South Africa, obviously Africa is not a country, South Africa being the country.

What are your tips for writing these settings? And why Africa?

Tony: Yeah, well, why Africa, I think because there’s that great adage that says, “Write about what you know,” but I think write about what you’re interested in.

And this is a continent that continues to fascinate me, you know, more than 20 years since I first visited here because it’s always changing. There’s so many different cultures, so many different countries. The countries that I write about within, broadly, Southern Africa, have also changed dramatically in some cases over the last 25-26 years or so.

So there’s plenty of inspiration there, which is important. I’m passionate about things like the continent, wildlife, and also social issues that are going on in some of the countries that I write about, and the politics. That’s my hook, I guess, and that’s what I’m interested in.

When it comes to setting, it’s crucial because a lot of the people who buy my books I’m sure just buy them because they’re set in Africa. I know so many of my readers who will just read every Wilbur Smith book or every Rider Haggard book or they’ll read everything that they can possibly find set in Africa. Perhaps they’ve lived it. Perhaps they’re an expat who’s moved to the UK or moved to Australia, and part of them misses their home country.

So there’s an interest in setting. Setting becomes like a hook for someone to buy a book, so it’s very important. I have come up with a few tips. I did a presentation on it recently.

The first thing I’d say about setting that I’ve learned is —

You have to make setting work for you. You have to give it a job.

It’s not just window dressing. It’s not just describing a lovely location or just to anchor a character in their scene.

Setting can show us how a character is thinking or what they’re feeling, and that’ll be colored and enhanced by the environment around them and how they view it.

You know, say a character is up or happy, they’ll revel in the rich beauty of the Savanna landscape, the wildlife, and they’ll be fascinated by the heritage and the people. But if they’re down or facing adversity or in danger, then you weave in things like the laden skies, the dirty streetscapes, the tatty old buildings, or that lion lurking in the long grass with the chilling golden eyes as a portent of doom. So you give your descriptions of location and setting a job, I think is something that I’ve learned over the years.

Then setting and place, they’re more than just the physical description of the landscape. I think people can fall into that trap of waxing lyrical about what the area looks like.

But of course, it takes in things like the history of the place, the politics and culture which go to the mood of that particular place and setting. It’s the people in the street, the music that’s playing, the public art or graffiti, the food on the streets, or the absence of food, what people are drinking.

When it comes to people, the different cultures, fashions, languages, and backgrounds of people are crucial in the sort of books I write. Quite often, these are sources of conflict as well as kind of celebration and enrichment in the countries that I live in. Quite often, things like culture and politics are life and death matters in the background of where I write my books.

Then of course, there’s the natural world. The wildlife, the birds, reptiles, the environment and the state of the environment, the problems with the natural landscape, which certainly are things that I touch on with things like poaching and environmental issues, and climate comes into it.

So the third thing I would say to people is—

When you’re writing place, use all of the key elements of writing, not just description.

Also use narrative and dialogue because with the narrative you can weave in a little bit of the history and the impressions of the streetscape and the country from your character’s point of view. Certainly use the description, this is your excuse to exercise your skill and your flair in describing a scene, painting a picture. That’s good, but also use dialogue.

I always say to people, a simple example is, rather than say it’s hot or come up with some metaphor for how hot it is, just have a character say, “I’m melting.” So work in a bit of dialogue into the setting.

If I can just continue, the fourth one, I would say, I always love to tell people, “Show, don’t tell.” I don’t have any tattoos, Joanna, but I always tell people when I’m giving writing courses or instruction that if I was going to have tattoos I would write, ‘Show, don’t tell,” on one hand, and I would write, ‘Trust the process,’ on my other hand to sort of keep me motivated each day. I think show, don’t tell is a good thing to keep harping on about it and to keep bringing back.

So when it comes to describing a setting, show us, let us feel it. Drop us in the middle of the bush or the marketplace —

Engage the senses, at least a couple of them at a time.

I mean, let’s have your character smell the street food cooking, or the musty dirty laundry smell of an elephant, because that’s what an elephants smells like, like if you’ve left your washing too long in the hamper and it’s all dead. Get that sort of thing in there.

There’s some good advice that I picked up from Stephen King’s book, On Writing, which is I guess if I could say, my Bible. I hope I don’t offend anyone by saying that, but it’s my go-to book is Stephen King’s On Writing. He talks about zooming in on the little things. Don’t just say the birds were singing, but give us the name of the bird and what its call is. Show us Charlie’s doll in the rubble of the burned out building.

In some of my books, I pick up the most amazing things as I travel and research. I put in one book, Safari, that’s set in the Democratic Republic of Congo, I had a character drinking Guinness and Coca-Cola, which is a particularly popular drink in the Democratic Republic of Congo. A few people messaged me after that saying, “Do people really drink Guinness mixed with Coca-Cola?” And they do. Stephen King says a few well-chosen details will stand for the rest.

The final thing I want to say about place is something I’ve learned the hard way — You’ve got to get it right.

This is our job, you know. We have entered into a kind of contract with the reader where if they want to be taken to another place, they expect it to be done accurately and faithfully, particularly if they’ve lived there themselves.

If you’re lucky enough to go and visit a place that you want to set your novel in, to travel as part of your job as a writer, that’s great, but you have to make sure that if you’ve got characters that are living in that area, that the places and the experiences are relevant to them.

Just a very quick example of that. I read a crime novel not too long ago by a very big name, a world-renowned crime writer, who had obviously been to Sydney, to my hometown, and they’ve obviously had a very good time there because this author had a character, an Australian character, who was a policeman, a Detective Sergeant who lived in a place called Brighton, which is actually called Brighton-Le-Sands. It’s not called Brighton, so that was a mistake, he kind of abbreviated that. But this detective sergeant couldn’t meet the lead character because he was taking his son sailing that afternoon at a place called Rushcutters Bay.

Now Rushcutters Bay and Brighton are at two opposite ends of the city. And Brighton is on Botany Bay, it’s a very good place to go sailing. So why this detective sergeant would be taking his son to Rushcutters Bay sailing in the afternoon didn’t make any sense. I have yet to come across a cop that owns a yacht in Sydney.

Joanna: Maybe in Auckland.

Tony: Maybe. I’ve yet to come across one who probably wasn’t crooked that would be able to afford membership of the Rushcutters Bay Club. So they’re all these like jarring references. The descriptions were probably spot on, but it’s about context, right?

It’s about getting things right, and it’s about context. And I would say to people, as I do whenever I’m talking about research, the same thing goes to place, is visit these places, read about them, learn about them.

The best way to research or to capture place accurately, particularly if you’re not from there, and this is the situation I have found myself over the years, is talk to a local.

Spend your time finding a local, online if you have to, and just ask them a few questions about their hometown and what it’s like.

So sorry, that was quite long, but that’s my five basic tips.

Joanna: Good tips there, but you know, I’m going to have to challenge you. Yeah, we have to talk about the ‘elephant on the podcast,’ which is, at the end of the day, you’re an Australian and you’re writing about Africa. You’re also a white guy. And obviously, there are a lot of white Africans, but there are also a lot of other people in Africa.

One of the things in this current writing climate is a perspective on writing authentically based on your own background.

Now, and also like you mentioned before, African fiction being a genre, and you mentioned Wilbur Smith, who, again, someone from the outside. So how are you addressing this? Has it come up for you?

How are you addressing it? And what are your recommendations for people?

Tony: Yeah, it sure has. And it’s a really, really good question. It’s very topical, very relevant as well, too.

Also it can be a tricky one because people will say, you know, you can’t appropriate a particular culture or a particular race or something like that to write about if you’re not from there. And yet, on the same hand, I don’t want to be criticized for only having like all white guys in my books because that’s not reflective of my readership over here in South Africa anymore.

The interesting thing is, there’s two strands to it, publishers are certainly becoming more aware of it. So my South African publishers will do a sensitivity read these days. They’re looking at sort of cultural aspects, any issues to do with race or background and those sort of things, which is good.

The other thing that I’ve found, from a personal point of view, my books have changed over the years in line with my experience. So my earlier novels tended to be about outsiders who found themselves in Africa, tourists or people visiting for work or something, who then got themselves in a bit of trouble because the books are thrillers, or got tangled up with poachers or something like that, because that was my experience, I was learning at the time.

As time has gone on, and I live here now most of the year, my circle of friends has grown. My readership has changed because South Africa has a really good vibe about it at the moment. Publishing is doing well and changing as socio economic standards and demographics and things changed here in South Africa. So there is a growing affluent, middle to upper class, I guess you would say, here of African people that has kind of emerged in the last 20 years or so.

They have more leisure time, more time to spend going visiting national parks, more interest in reading fiction. There’s quite a boom here in African women’s fiction here at the moment, which is fantastic to see. And what I’m finding is my readers here in South Africa are from the various African cultures, from the Indian culture, from the English-speaking South African culture, from the Afrikaans-speaking South African culture, and they’re my friends. So I feel like a need I have to tap into those cultures and reflect them in my writing.

So I go out of my way to do my own sensitivity checks.

You know, it’s a really important thing to say, and it’s not to be glossed over because when I have seen when I’ve done a bit of mentoring, and if I’ve seen other people talking about some of the cultures, I want to ask them, “Have you actually checked a lot of this stuff?”

It’s not good enough to go online and say, I’m going to have somebody speaking a few words in an African language. This is a mistake I’ve made. Well, this was a mistake that was caught before publishing, but I had a book set in Zimbabwe called African Dawn, which is a bit of a sweeping saga over 50 years of Zimbabwe’s tumultuous history and all the politics and conflict that have gone on in their country. And I’m lucky, I’ve got quite a few Zimbabwean readers.

I got a lady called Takram Woodsy who was living in Australia to check this book. And thank goodness I did because I had things like I had a character greeting another character, she was a female character greeting an older male, and she says to him ,”Kanjani,” and Kanjani is hello in Shona. It’s like in Australia it would be ‘G’day’ or ‘How’s it’ or whatever. And she said, no, no, no, no, no, you can’t do that. She says, she has to say ‘Mangwanani baba,’ which is ‘good morning, father’ in the formal tone and with a term of respect, because it just jarred her to the core. And she says, you can’t do that. And here am I waltzing around Zimbabwe saying Kanjani to everybody I meet.

You’ve got to have a little bit of knowledge. And the other thing, Joanna, is a little bit of knowledge can be a dangerous thing. Again, it’s about research and researching place.

I don’t even like really do a lot of research when I’m writing. If I don’t know something, like a piece of language, or even a technical thing, like how to stitch up a wound or fly a helicopter or something, I just leave it blank, and just put ‘check’ in my manuscript, and then I read search retrospectively. So after I’ve done the first draft, I’ll go out and find a person.

I’ve had about six people read my forthcoming book, a book called Vendetta, which is set partially in the 1980s in South Africa, when the country during the apartheid era was engaged in a war in Angola.

And I’ve had quite a few people read this book for accuracy and sensitivity because the best way to research is talk to people. I am 100% convinced of that after 20 years, that that is the best and most accurate way is to find a subject matter expert, or someone from that culture or community, to read and check your work, if they’ll do that. I find people are very generous. It’s probably more work than reading lots of books and researching online, but the human element is just crucial for me on that sensitivity side of things.

Joanna: And obviously, you love the research process, too. I mean, that obviously comes through in what you’re saying. I also love the research process. So I think research and respect, respect for all of these different cultures. Of course, Africa, particularly every single African country has so many different groups as well.

You can’t possibly know all these things, whoever you are, you cannot know everything. So yeah—

Respect and research. I think that those are really good tips.

Tony: It’s a beautiful way to put it. Yeah, I must say that’s a really, really good way to put it.

Joanna: I certainly encourage, as you do as well, we encourage people to write about things outside of their own culture and experience because, like, why would we be fiction writers otherwise? It would be so boring. But yes, those are some ways to avoid trouble.

I also want to ask you, you’ve mentioned the wildlife, and you’ve said that your books include social issues, politics, the environment, and many authors want to bring attention to causes they care about, but equally, these things can turn into like a lecture. And it’s like, oh, gosh, not another book bashing on about the environment when I just wanted a thriller.

How do you balance writing a compelling story and then advocating for things that you want to bring attention to?

Tony: Yeah, another really, really good question. And I think there was something I read, it might have been in Stephen King’s book, that the story is king. I don’t know whether that was a play on words, but you got to keep the readers turning the pages.

Whether it’s comes to describing a location, or history, or having to give some historical background, if you get too bogged down, the reader is going to stop turning the pages. And the same thing goes for causes as well.

I am passionate about those things that I mentioned about wildlife and some socio economic causes and politics, but I am acutely aware that within my readership, there are people on the polar opposite sides of these issues. I don’t want to alienate anybody for commercial reasons, but I want to kind of be honest.

As I said, I did work as a journalist for a few years. I don’t think there’s an awful lot from having worked as a journo that really helps you to write fiction, but I would say the two exceptions to that are dialogue, because you kind of get taught and used to putting words in people’s mouths as a journalist. You get used to capturing spoken speech in a written format.

But the other thing is balance. And when I present an issue, say rhino poaching, which is an issue that comes up in a few of my books. Rhinos are killed for their horn, and it’s a big problem here in South Africa because this is, unfortunately, where the last most of the world’s rhinos live here. So this is kind of Ground Zero.

There is an ongoing debate in Rhino conservation about whether or not to legalize the trade in Rhino horn. I have my personal views. I’m actually opposed to it, but many of my friends are vehemently in favor of it. And so when it comes to an issue like that, I try to weave in both sides of the debate. Again, in a respectful manner, as you say.

So I will have a character who is kind of pro-trade, pro-legalization in trading rhino horn, and I’ll have one who’s stridently against. I’m sure that, I hope at least, that the pro-trade people look at their character and feel more sympathy for them than they do for the other one. And the same thing comes with politics as well, too, because like I said, politics is a life and death business over here in some countries.

Joanna: For sure.

Tony: And so, I am not kind of afraid of stating things, but—

I try to approach it as I would if I was a journo: objectively, with balance, and respectfully.

So you don’t go into a diatribe about why this particular policy or politician is bad, but you try and show the effects that their policies have had on an individual person. Like Stephen King says, zoom in.

So if you see people obviously poorly dressed, they’re starving, they’re perhaps begging for food, and you see a politician driving past in a brand new Mercedes Benz, you don’t have to be told there’s something wrong with that scene. You show, don’t tell. People reading that will nod their heads and say, yeah, that’s accurate. That’s pretty well how it is in some of the countries that I write about. So you fall back on the good old show, don’t tell.

My editor and publisher are very good at putting little notes in the side of the margin saying, “Stop downloading, Tony. You’re downloading information.”

Joanna: That’s the problem when you love research, right? I want to tell you everything.

Tony: It’s the classic trap, isn’t it? And we’ve all fallen for it.

Joanna: But then I would say as a reader, like I grew up with Wilbur Smith as well, and Rider Haggard, and I actually loved that. I’m sure you’ve heard me talk about how I went to school in Malawi, and so sort of reading about Africa, and that’s how I came to know of your books. Connecting with you is quite thrilling for me because I’ve seen your books for years. So that’s quite kind of cool, you know. That’s because of reading books set in Africa that I’ve done since I was a child.

Tony: Fantastic. Yeah. And I think if you look at someone like Wilbur, who is unfortunately passed away, but the books of his that I like the most were those early ones set in the 70s and 80s, when he was writing a lot about contemporary Southern Africa and the issues that were would be at the time. And I think that’s what strikes a chord with people, as well, because it’s a funny continent as you’ve been acutely aware. There’s lots of problems here. There’s crime, and corruption, and political mismanagement, and poverty, and health issues tend to be exponentially worse here.

The interesting thing about this continent, it comes back to the people, is that I think if there’s one thing that struck me that’s greater than the scale of problems that people face, and you would have no doubt scene this yourself, it’s the ability of good people, more often than not at the village level or the grassroots level or the volunteer level or the park ranger level, to just come together and do the most extraordinary things. They go out of their way to get their children in education, sacrifice so much so that the next generation will be better off.

In the case of rangers in the anti-poaching area, they literally put their lives on the line to protect wildlife. That’s the sort of thing that I like to capture because that’s what kind of inspires me. That’s what I used to like reading about in some of those other African books as well too, that kind of raw effort at the grassroots level of people to sort of do the right thing.

Joanna: The other thing, I mean, you’re talking a lot about the historical aspects of Africa and South Africa, but I mean, things are obviously very different now as well, in that it has one of the biggest mobile economies, that leapfrog idea of tech where everyone’s using mobile payments and mobile, not even banking, just mobile apps for money.

And we were reading this article the other day about blood delivery by drone, like the drone deliveries in to places in Africa is really exciting. And we can’t do that here because different regulations and just overcrowding and things like that. And, of course, Nigeria is one of the fastest-growing economies in the world.

So I feel like another issue is how people are thinking, and like you say, if they haven’t visited places. How do we avoid the stereotypes? Because I feel like books written about like 1980s South Africa, for example, that’s just not the reality of what South Africa is now. And any of these countries have just changed so much, and I’m sure there are still some people living in some areas where it hasn’t changed.

How can people avoid writing stereotypes about place?

Tony: Yeah, well, I think when it comes to travel, like if you’re lucky enough to say I’m going to go on holiday to South Africa to research as well, one of the problems is you might end up cocooned.

You might end up stuck on the luxury private game reserve or something like that, and you won’t see what’s going on outside in the big wide world. I’m not advocating that people, you know, go out to areas where they might not feel safe or comfortable, but it does go to talking to people. That’s something that I keep coming back to is that my best source of research is human beings, is talking to people.

To give you an example about not falling into stereotypes as well, too, is during lockdown, I read a book called Blood Trail. Blood Trail is like a couple of my other books about rhino poaching, but it’s about a particular aspect of that struggle is that poachers, and sometimes Rangers, will enlist the help of traditional healers, sangoma, to give them talismans, or medicine, or potions, if you like, that they believe will increase their chances of surviving in the bush. Whether that is they’re a Ranger or whether they’re a poacher, they will buy a potion that will make them invisible or will turn them into an animal to avoid detection or to avoid being shot. And these are serious, serious beliefs.

Now, many people will just dismiss this out of hand. And to those sort of people that say, well, that’s a load of nonsense, I’d say, have you never prayed? And there’s a wonderful saying that there are no atheists in foxholes. People do turn to religion and other belief systems in the context of high-risk, high-reward environments. And that can be a war zone or it could be going out in the bush trying to kill a rhino and being against armed Rangers.

So the way I got around that, and the way I did my research for that book, was to have some pretty in depth conversations with some friends of mine about their belief systems. And in the course of doing that, I was able to get so much rich information about their current attitudes to politics and how the country was going, just by conversations.

I think one of the great things about being a writer, and it sort of is the same as being a journalist, is that you kind of have a license to ask the most in depth and personal questions of people. And that’s the best way to avoid stereotypes because you’re getting the information straight from the person’s mouth and from the heart.

I was able to learn so much more about some of my friends by asking them, “Hey, do you believe in traditional medicine? And would you use it yourself and why?” And again, I found so many parallels with Western culture, and our belief systems, and superstitions and things like that. So that’s how I try and avoid it. You know, it’s that human contact, that human element.

Joanna: Fantastic. Well, there’s so much we could talk about, but we’re out of time.

Tell people where they can find you and your books online.

Tony: I’ve got my good old website, which is www.TonyPark.net. I do sell wide, as we said, everywhere outside South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. So yeah, I’m online, on print, audio, and eBook everywhere. So TonyPark.net is my home base.

Joanna: Fantastic. Well, thanks so much for your time, Tony. That was great.

Tony: Thank you so much, Joanna. I really appreciate it. And can I just say again how much I enjoy your podcast. I think we talk a lot about social media, and I love through social media that I have a direct conduit to my readers and we can have a genuine conversation with each other. And podcasts such as yours and others I’ve learned through your podcast are so great because now as authors we can have that same level of communication with each other and learn from each other. So thank you for everything that you do.

Joanna: Thank you.

The post originally appeared on following source : Source link