Podcast: Download (Duration: 52:29 — 42.2MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | TuneIn | RSS | More

What are the crucial linchpin moments in your novel and how can you keep a reader turning the pages? John Fox gives fiction writing tips in this interview.

In the intro, writing and publishing across multiple genres [Ask ALLi]; Pilgrimage and solo walking [Women Who Walk]; My live webinars on using AI tools as an author; Cowriting with ChatGPT: AI-Powered Storytelling by J. Thorn.

Today’s show is sponsored by ProWritingAid, writing and editing software that goes way beyond just grammar and typo checking. With its detailed reports on how to improve your writing and integration with Scrivener, ProWritingAid will help you improve your book before you send it to an editor, agent or publisher. Check it out for free or get 25% off the premium edition at www.ProWritingAid.com/joanna

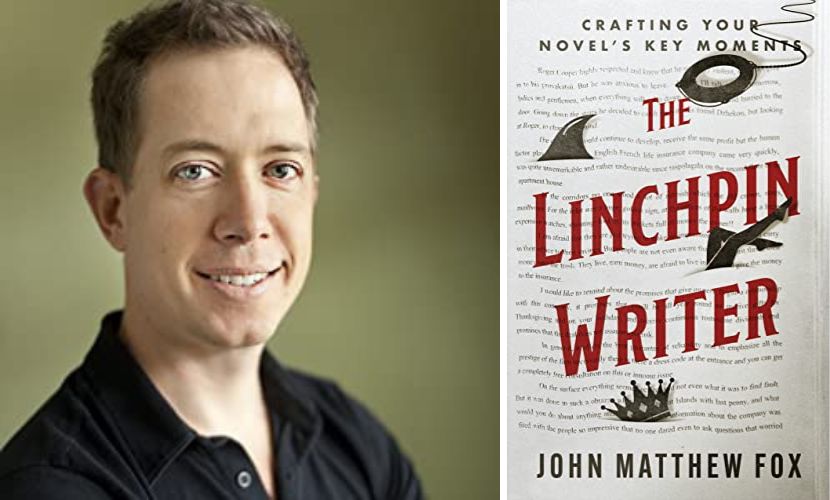

John Matthew Fox is an award-winning short story writer, a developmental editor, writing teacher and blogger. His latest book is The Linchpin Writer: Crafting Your Novel’s Key Moments.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- Writing a book based on a blog — what needs to change?

- Linchpin moments and why they are important

- How to write emotionally moving stories

- The difference between scenes and chapters

- How to write wonder

- Writing better endings

- Using AI tools when writing fiction and editing

You can find John at TheJohnFox.com or on TikTok @johnmatthewfox. John has courses for writers here.

Transcript of Interview with John Matthew Fox

Joanna: John Matthew Fox is an award-winning short story writer, a developmental editor, writing teacher and blogger. His latest book is The Linchpin Writer: Crafting Your Novel’s Key Moments. So welcome back to the show, John.

John: Thank you, so wonderful to be back.

Joanna: Yes, indeed. Just in case people don’t know you—

Tell us a bit more about how you got into writing and publishing.

John: I started my blog way back in the day, 2006, just to join the literary conversation. And over time, it evolved from a blog on literary news and commentary into more of a craft blog, just helping writers with their novels, short stories, children’s books, any sort of fictional storyline.

Now, I’ve been editing for quite a while for authors, doing developmental edits. I offer courses, both on-demand courses and live courses. I’m starting up a publishing branch, which is self-publishing assistance, I like to call it. Not traditional publishing, not vanity publishing, but something in between.

Joanna: There’s certainly a call for all of that. Your courses are great. I think you’ve got some fantastic information on your site.

Is this the first nonfiction book you’ve done?

John: Yes, it is. I had the short story collection, and then the nonfiction book just came out in October, so it’s relatively new. I’ve been getting lots of feedback from writers who have been enjoying it and using it to write their books and revise their books. Those are lovely emails to get.

I guess I’d been helping writers in one way or another for a whole decade through emails, and articles, and developmental editing and whatnot. So I’m like, well, why don’t I try to put down some of the things that are most helpful for writers. Why don’t I try to put that down on the page?

I have a good amount of stories about the writing life as well, so I thought I’d include those so it’s not just cut and dry, boring, do this and do this craft information, one, two, three. I think it has been helpful for writers. It’s been a joy to interact with them on another level.

I do think nonfiction, in general, is a lot easier for me to write than fiction is. There’s so much imagination that has to go into fiction, and so much plotting and characterization. Nonfiction, man, I just sat down and wrote it. It just spilled out so easily, so it made me enjoy the process of writing quickly.

Joanna: We’ll get into the book in a minute. I know a lot of people listening, they might also have years’ worth of blog posts and articles, and you have a lot of really well-crafted articles on your site.

How did you turn some of those into a book? Or did you start from scratch? You know, because a while back there was this sort of ‘from blog to book, just output your WordPress files into a book format.’ And it’s like, no, that’s not how you do it.

Did you use elements of your blog articles and rewrite them? Or did you start the book from scratch? What was that process?

John: I definitely started from scratch because if you know anything about how to write for online media, it is just vastly different than writing a book.

You definitely can’t take that blog post and just throw it in a chapter and be like, alright, I’m good. It doesn’t work like that at all.

So what I did is I took topics that had been really important to my readers, certain topics that I’d written a post on, and then I just wrote on that topic, but completely from scratch.

I don’t think I used a single sentence from the blog inside the book. It’s all new stuff.

Then there was some stuff that wouldn’t work as blog posts, like, I don’t know, like writing about wonder or writing about emotion, like that’s stuff that people aren’t going to search for. It’s really difficult to write a blog post about that, but they work really well inside of a book.

That’s probably because not a lot of authors talk about them or not a lot of authors like study those topics. So the book gave me a lot more latitude to go into areas that I hadn’t been able to cover with the blog.

Joanna: I think that’s good advice. I do think starting from scratch is a good idea.

Okay, let’s get into the book. So the book is called The Linchpin Writer.

What are these linchpin moments, and why are they important?

John: So linchpin refers to these little pins that go inside the hub of a wheel so it doesn’t fall off the axle, right? That’s the original term, and then what it’s become is a term that refers to like really key people or objects or ideas inside of an organization.

I think a linchpin moment inside of a book is a make-or-break moment where the reader might stop reading, or if the reader doesn’t like that particular scene, it’s going to ruin the book for them.

So they are the most key places in your novel where you absolutely have to get them right. So as writers, we should probably concentrate on those places more and make sure we really nail them.

It’s stuff like when you became a writer, it’s a death scene for a character, it’s stuff like romance, or a particularly climactic romantic scene. It’s describing a character for the first time, or ending a chapter, or ending the whole book.

All of these are really critical moments whereas the writer, you’ve just got to nail it, you got to nail them to make your reader happy.

Joanna: Well, first up, you mentioned a linchpin moment for an author, and I think that’s really interesting.

In the book, you say, “when they became a writer,” and I find this a very interesting phrase, “became a writer,” because to me, these days, there are a lot of different routes to market. I mean, someone might be a blogger for a decade, that makes them a writer, but that doesn’t necessarily make them an author. Someone might have millions of Kindle page reads, or millions of views on Wattpad, but no physical book, and these days, obviously no traditional publisher.

What do you mean by a linchpin moment for the author? And how might people measure it?

John: I don’t think the medium is very important, right? I mean, if they just have millions of eBook reads, or millions of reads online, that doesn’t matter to me as opposed to a print book. I feel like if you’re writing, you’re a writer. And if people are reading your writing, in whatever form, then you’re an author. You know, I don’t think it’s super, super complex.

I think, ultimately, writers feel nervous about calling themselves writers because there’s this crisis of confidence inside yourself.

And I’d say just, hey, summon up the inner confidence, like you are writing, you’re putting words down on a page, they will find readers if they already haven’t. So just call yourself a writer and feel confident about that.

Joanna: Easier said than done!

And actually, I do think this is important, because I’ve been talking to a lot of people, and after the pandemic, including myself, we haven’t necessarily been writing a lot because of various reasons, mental health reasons or burnout.

There are a lot of people, myself included, who make a good deal of money from backlist books. So actually, you can still be an author and not be an active writer. So actually, I think these definitions become important when your self image is based on these things.

John: You mentioned people taking breaks or not writing for a time, and I actually think that’s key to being a writer. I think a healthy writer takes breaks.

I mean, after my first book, I didn’t write any fiction for a while. I think I probably, I don’t know, I was burned out, or the book didn’t launch with the fanfare I expected it to. I had to recalibrate my expectations for being a writer and come up with a new project to work on. To me, that’s not an aberration.

You’re not failing as a writer if you’re not writing for a time period. Life happens.

Parents get sick, children are born, like, it’s fine to take a break from writing. I think writers end up having ideas and coming back to writing at some point, that’s what makes you a writer. I think people shouldn’t feel ashamed just because they’re not writing for a period of time. Like, that’s part of the writing process.

Joanna: I like that because one of the most common questions I get is, “Oh, so you say you’re a full-time author, but how much time do you actually spend writing?” As if that’s the thing that will make a difference to being a full-time author.

Let’s move into the book, so someone is getting into their novel. You talk there about some of the linchpin moments, now for me, with fiction, the opening of that first chapter, really is a linchpin moment.

What are some tips for getting the linchpins of the beginning right?

John: You’re absolutely right. That first chapter is one of the biggest linchpin moments because, you know, you don’t write it right, and suddenly the readers sets your book aside and never returns to it.

So in the book, I talk about four different steps that you want to get in that first chapter. One of them is characterization.

I think you have to deliver a character which is set apart from other characters, who seems unique, who is doing something a little bit out of the norm, something strange, something that attracts us to a character and makes us think, yeah, yeah, I’d like to go on a journey with them.

Another thing I think that’s really important for the first chapter is your energy or your tone.

This comes through just the type of sentences you write, what you’re talking about, whether there’s a chase going on, whether there’s conflict on the first page. Like, what is the feeling that the reader gets from reading this first chapter? Is it grim and dark? Is it ebullient and exciting? You know, you’re setting expectations for the rest of the book.

I feel in many ways that —

The first chapter is a promise to the reader.

You’re telling them, “Look, this is what this book is going to be like. Here’s the style of writing. Here’s the character you’re going to fall in love with, or hate.” And you want to fulfill that promise for the rest of the book.

I think a third thing would be some sort of mystery. It doesn’t have to be a classic mystery, like who done it, like who killed the butler. Just any sort of question that the reader has about, oh, what happened in this character’s past? Or what is going to happen in the near future? Something that makes the reader wonder about the storyline.

Then I’d say the fourth one would be emotional resonance. What does the reader feel like in this chapter?

If your first chapter doesn’t make them feel something, whether sorrow or happiness or jealousy, like any emotion that you can evoke from the reader. If you get at least one strong emotion from the reader in your first chapter, there’s like such a higher chance that they are going to continue reading for the rest of the book.

Joanna: Yes, that beginning really has to signal the genre, and I have to know that, yeah, that’s a book I want to read. I guess it should also tie in with the cover.

I feel like I sample a lot of books based on the cover and the description, but then a lot of the times I start the sample, and I’m like, oh, that’s not what I expected. So I guess that’s a hint for people around book marketing, is these things have to work together.

It’s not just a great cover. It’s the cover, and the blurb and the first chapter. Right?

John: Yes, if I had to choose between an incredibly beautiful cover that sort of misled readers to what the book was about, and like a pretty plain basic cover that actually matched what the content of the book was, I’d choose the plainer cover, right?

Because the cover is also a promise to the reader about the genre, about what’s going to happen in the story, about the characters if you’re showing a character on the cover. Like all of that stuff is setting the reader up so that when they get to your book, they’re prepared to read it.

Joanna: It’s interesting, you mentioned emotional resonance there. This is all tough to get in the first chapter, right? So I mean, you can’t really put everything in one chapter. But I was thinking about Colleen Hoover, I mean, her books really are so popular because she is so emotional.

What are your tips for writing these emotionally moving stories?

Because not everyone wants to write gritty romance.

John: When I talk about emotions, I’m talking about like any emotion, like making the reader feel anything, from anger, to sadness. I mean, it definitely doesn’t have to be romance. So I think there’s some common mistakes that writers make when they’re trying to make the reader feel something.

The most common mistake is just showing a character feeling that emotion. Like the best way to get your reader to cry is not to show a character crying, that actually doesn’t transfer. Like we can see a character crying and be like, oh, like, okay. But if you show them in a situation where we think we would feel sad, then we’re going to feel that sadness, whether the character is crying or not.

For instance, I was just reading The Great Passion by James Runcie about Bach. There’s this poor kid who goes to a music school, he’s starved, he’s beaten, he’s bullied at this all boys school, and I like really felt bad for this kid. Like he’s just going through the worst experience at this boarding school. Now, I didn’t need him to like cower in his bed every night and cry for me to feel that emotion as a reader. I felt that emotion because there was a situation that was terrible for him, and I pitied him.

So I think it’s important to focus on situations in your book that are sad or happy or jealousy-inducing, or whatever, rather than just characters feeling that emotion.

Joanna: I mean, is curiosity an emotion? That’s what I want in a first chapter. I want to feel curious about an open question.

John: I think my point about mystery probably fits best with the idea of curiosity. You know, there’s something that you don’t know and you’re interested to learn more. Absolutely, that’s key for a first chapter.

Joanna: Then I was also just thinking about James Patterson. Obviously, he’s famous for writing incredibly short chapters. You think about James Patterson’s books, reading one of his chapters is a masterclass. In fact, he has a Masterclass on it. But he manages to get all of that in one chapter.

John: I think he does a great job with starting chapters and ending chapters. You know, both of those are some linchpin moments in your book. How do you get the reader in? Do you start in the middle of a scene? And then where do you end to make the reader turn to the next chapter?

I think having short chapters makes readers feel smart because they feel like they’re reading faster.

It also gives these really bite-sized narrative bits that always make you want to turn to the next one because it’s very low obligation. Because sometimes if you read a long chapter, and you’re like, well, I don’t want to start a whole other giant chapter, but if it’s a really short chapter, you’re like, well, just one more, and just one more, and just one more. You know, it’s tough to stop reading.

Joanna: And actually, this is a good tip that you mentioned there, splitting the scene between chapters.

I think we write in scenes as fiction authors, but when we structure a book, we structure in chapters, and they’re not the same thing.

Maybe you could explain the difference between a scene and a chapter, and how we could maybe create a linchpin moment by splitting a chapter.

John: Well, I think writers often think that the end of a chapter is the end of a scene.

And the best place to end a chapter is at the beginning of a scene, when characters arrive, or when some new information happens. Because then if you split it right there, the readers like, oh, well, I want to turn to the next chapter to continue this situation. It’s very non-instinctual to end a chapter that way, but I think it’s the best way to end a chapter to keep the reader reading.

As far as the difference between scenes and chapters, it depends on how long your chapters are. You might just have one scene or a couple scenes per chapter. I mean, you could structure in so many different ways, like a chapter could be in a singular place, but there’s like three different scenes within that place.

I think what’s key for scenes is making sure there’s a reason why you’re breaking that scene. A really good reason to break the scene is because you want to skip the boring parts.

You know, sometimes my authors that I edit for, they’ll have a scene and it sort of feels like the end of a scene, and then they’ll do like connective tissue. They’ll write, like, “and then this person went there,” or, “then they did this,” or something like that.

And I’m like, no, you should cut that whole section, put a little asterisk in there, and just start once they’re already in the new place or once they’re already in the next part of the action.

So what scenes allow you to do is to cut all the boring connective tissue and just focus on the absolutely best parts of your story.

Joanna: I guess, just to be basic about it as well —

A scene is a character in a setting, performing some kind of action for a reason.

That’s just a basic description. Is that how you describe it?

John: Yes, I would describe it that way. Sorry, I feel like I always jump to something I haven’t heard before. I feel like I’m often giving advice to authors who, I don’t know, maybe have a little bit more experience under their belt.

So yeah, that’s a great basic definition of a scene. In a particular place, doing something, there’s some conflict happening, there’s some tension happening. There’s some dramatic action.

Sometimes, like a character just sitting by themselves thinking really isn’t a scene, right? Something needs to happen, they need to do something, they have to talk to someone, there has to be conflict with someone, otherwise the scene doesn’t really work.

Joanna: Absolutely. So let’s get to some of the other things. You mentioned wonder. There is a chapter on wonder.

What do you mean by wonder? And what are some examples and ways to write it?

John: Man, sometimes when I’m reading a book, I just have this experience of laying the book down and sitting back and being like wide-open-mouthed and being like, woah, like, this author is so good. Usually they’ve described something that’s just incredibly beautiful, or like a crazy scenario with bioluminescent waters that just like wows me.

I love those moments as a reader where I’m just flabbergasted about how cool this book is right now. So I wanted to think about, as writers, how can we create those moments?

And I think it’s really important to give like otherworldly senses. If you’re writing something like sci fi, or fantasy, or even literary, I think it’s easier to get to those otherworldly moments because you’re writing such fantastical stuff. But I think it’s equally possible in realism or historical or romance, because the job there is to take everyday life and make it feel strange or wondrous to the reader.

Like how can you take something which the reader experiences every single day and make them feel it in a new or different way? I think that’s really the job of the writer is to take these experiences and make the reader feel something and experience something that they haven’t before.

Joanna: So how do we do that? Is that through sensory detail or through metaphor?

John: I think you can do with metaphor if you are describing extremely different things. I read this author once you described a flock of birds rising up from a tree all at once, like a net. And I’ve always loved that metaphor. And every time I see birds rising from a tree, I see her metaphor. Now I see this very thin mesh net rising up and falling down.

I also think you can do it through description. I feel like description is one of the main ways to create wonder. If you describe something really well, especially if it’s something strange—like I’m thinking of Cormac McCarthy describes all these men riding through the desert between the US and Mexico, and there’s like little lightning bolts, little frictions of electricity that sort of are running all over their clothing. So it’s completely dark, but there’s these little blue flickers all over their bodies and the bodies of the horses. And I just imagined that and thought, wow, that’s really crazy, and really beautiful. Yeah, that made me feel wonder.

Joanna: That’s interesting. I mean, the examples you’ve given are more literary fiction, really. Are you expecting that in genre fiction?

John: That’s a good question. I guess it depends on the author. I do think you can feel wonder at a romantic relationship. You can feel wonder at like the beauty that their love is finally coming together, something like that.

I think if you’re writing like a historical novel, or something that’s more commercially based, describing like a bustling street with all the wares and people selling things, like that sort of level of description I think can make the reader be like, woah, like, that’s a really cool place. Like, I’m glad I’m reading about this book because it’s transporting me to a new location and giving me all this fun information about this.

So any type of world-building you’re doing or anything where you’re introducing the reader to something that’s strange to them, I think can create wonder. I think that applies for commercial books as well.

Joanna: Me too. It’s interesting because a lot of my book research is around trying to make these moments, because that’s what I look for in books, and trying to kind of think what would my readers really love reading about. So I try and find cool settings or cool things that I can write about that make people go, wow, that’s really awesome.

So I think, just on that though, some people find that difficult. I was going to say about book research, you don’t have to make it up from your brain, you can go on to YouTube. Like I wrote a scene in my thriller End of Days, which was about this Appalachian snake-handling church. I watched YouTube videos and took loads of notes, but I mean, it’s just like a ‘wow’ situation.

I’d see what these people were doing and I’d just try and capture that in writing. So I guess that would be a tip. You don’t have to make these moments of wonder up, you can go looking for input into your brain.

John: That’s exactly right. Yeah. I mean, snake handling is real, like it happens. And yeah, to watch that actually happen on the page, I think would definitely inspire a sense of wonder.

Joanna: And then we talked about endings of the chapter, but the ending for the whole book is also really important. I mean, personally, I really need a resolution in my ending. Some people like cliffhangers at the end of a book, I do not.

How can we write better endings?

John: Well, whenever I have an author who tries a cliffhanger at the end of their book, they almost always do it a little wrong.

So let me give a little piece of advice on that. You can include a cliffhanger at the end of the book, but it has to be like a sort of minor storyline cliffhanger, if that makes sense. Like you have to end the book with some sort of resolution to the main problem or conflict that’s been happening for the whole book. Right? You can’t leave a cliffhanger about that.

So as long as you end the book and satisfy the reader on all the levels, all the mysteries that they were wondering about, all the major plot points, as long as you satisfy all those things, then I think it is possible to give like a tiny cliffhanger at the end of the book.

The trouble is when people try to make like some major part of your story, not resolve it, and leave it as a cliffhanger. No, no, no. No one’s going to read the next book because they feel so unsatisfied with this book.

So usually when I recommend cliffhangers, it’s not at the end of the book. Usually they are for the ends of chapters. I feel like that’s the proper place for cliffhangers.

I feel like your sole goal at the end of the book is not necessarily to set the reader up for the next book, but really to make sure that this book resolves well and leaves them with a good emotional feeling, and that way they will read the next book.

Joanna: And also —

Be surprising, but not too surprising.

I always use the example of Stephen King’s Under the Dome. I’m not going to give any spoilers, but I read all the way through that book, and then when the ending happened, I was like, that was the wrong ending. I don’t know if you read that one, but I love Stephen King.

John: No, I haven’t. I haven’t read it. But I like what you said about surprising. I tell people it needs to feel both inevitable and surprising. Like when readers get there, they have to think, of course, it couldn’t have been any other way, but also, they couldn’t have predicted it. And those are two very contradictory things.

If you’re setting the reader up for the ending, then the danger is they’re going to guess it, and it’s not going to be surprising. But if it’s almost too surprising, the reader is going to feel like that doesn’t feel real, I don’t believe your story, you just did that to mess with the reader. So it’s really holding both of those things in your hands when you’re writing an ending, both surprising and inevitable.

Joanna: Well, it’s interesting because it is hard to write a novel, and many of us use various tools to help us when we write.

There are plenty of books, obviously yours, I’ve got a book on How to Write a Novel, and then there are books that can help us with plotting and emotion and blah, blah, blah. And now, as we record this in April 2023, we have tools like ChatGPT, which is AI-powered.

Now, you came on the show in 2021, and we talked about NFT books. You have definitely kept up with the tech and you’ve actually got some blog posts on how novelists can use ChatGPT.

Tell us how you think novelists, and authors in general, can use these tools and your thoughts on using AI with fiction.

John: I think all writers are underestimating the way that AI is going to radically change writing.

I think very, very few writers have really grappled with the enormous sea change which is going to happen. And not like enormous sea change which is going to happen in five or 10 years, the enormous sea change which is going to happen in like six months or a year.

I’m talking about people writing a book in a week with the assistance of AI. I’m talking about basically all copy editors and proofreaders being put out of work because AI is going to do your copy editing and proofreading. I mean, those are the big-level things, but there are tons of small things as well. Everything from if you’re having trouble describing a certain place, like ask AI to describe that place for you.

Maybe you don’t like how they write it so you rewrite it in your own voice, but then you can also get AI to write something in your own voice.

Describe how you want it to be written. Like write it more colloquially, or in a breezy tone, or write it in a gritty 1920s style noir tone. You can get AI to mimic all these styles of writing as well.

I mean, I just wrote a post on 26 ways that writers can use AI, and it’s everything from writing the summary of your book, to writing your query letter, to describing things in your book, to developing your characters. I mean, it’s like Google on crazy steroids is the best way to do research, that’s for sure.

The one thing I’ve discovered it can’t do is give developmental advice, though. It’s great at copy editing, it’s not so great at line editing. But when I asked it to developmental editing on a chapter in a novel, a short story or a children’s book, it gave really bad advice.

Joanna: Well, that’s at the moment, I mean, we are recording this in 2023. So if you’re listening in the future, that may not be true anymore because it’s about the context window of how much you can feed it. In GPT-4, it’s a lot bigger.

So you could pretty much do a novella now with GPT-4, which is in the paid version, because the input is a lot bigger so it has a lot more it can review. But of course, a full-length novel, you can’t put 100,000 words into the chat box for it to think about.

[If you’re interested in this, check out ChatGPT 32K, and also Anthropic’s Claude with 100K. Both of these are expensive at the time of publishing this, but costs will keep coming down.]

John: No. I mean, I’ve been using ChatGPT-4 and it wouldn’t even allow me to put 16,000 words in there, and I have the paid version. So I don’t know.

Joanna: The playground, the API.

John: But the problem isn’t putting enough in there, the problem is when I ask it to critique point of view, it can never say like, “You’re doing great with point of view. Point of view is great.” Like it’s mimicking what a developmental editor does, so it says, “Oh, you’re in limited third. Here’s what you can do to change it.” Sometimes that’s not the problem, right?

So it’s a little weak on problems of judgment and taste. While it’s really good at following the rules, which is why it’s amazing at copy editing.

But you’re absolutely right. Like this is the first iteration, like, we’re only at the beginning, what’s going to happen in a year? In three years? In five years? Like, the exponential growth is going to be pretty crazy. It’s going to get smarter much faster than we think.

Joanna: Personally, I feel like I’m excited, and I feel like it’s an augmentation of what I can do. I can move much faster with the help of GPT-4.

One of the cool things I’ve been doing, I was just checking to see if you’ve put it in, I don’t think you have, is that I can actually interview a character who is a certain thing that I don’t know much about.

So for example, I’ve got an urban explorer in my next novel, and I said, “You are Maxine, who is this urban explorer in Edinburgh. Using your knowledge of platforms and chat rooms and things, respond to my questions as if you are Maxine.” And this was so good, because you know, we struggle to write the dialogue in the voice of a character we might not know that well.

In the past, authors have written character bios and stuff like that, but this is actually almost channeling the voice of someone and it’s coming back with words that I wouldn’t have used myself because I didn’t know them. And I’d have to do a heck of a lot of research to find the right words. So this kind of channeling of characters is really interesting.

John: Oh, that’s brilliant.

Joanna: It’s really fun. It’s really fun as well.

John: I mean, the ability to talk with your character, that’s so cool.

Joanna: It is very cool.

John: You might not even use what they actually say, but it’s giving you their language, it’s giving you their perspective, like it makes it much easier for you to write them.

Joanna: Exactly. And then I’ve been using it for loads of things, like coming up with different monsters, combining different monsters. I’m writing a monster book at the moment, it’s called Catacomb, it’s a standalone horror book.

And coming up with, what are the different monsters in these different cultures? And how could we combine them together? And what could be the names? Like names are really good as well. What are the names that mean this or that or the other?

John: Yeah, yeah, I’ve played around with world-building aspects as well. You know, Tolkien took decades to create all the languages and everything of Middle Earth, and I can say, “Hey, create a language that mixes Sumerian, Turkish and Pawnee Native American dialects. Like create the alphabet, create the 100 most common words.” Then get DALL-E or Midjourney to draw you a map of your fictional land.

Like, it’s so easy to have all this stuff generated now. And you’re like, oh, wow, now I have a language, and a culture, and land, the species, the languages, the cultures. You can just ask ChatGPT to make all this stuff up, or to give you five or ten examples, and then you pick the one you really like.

Joanna: Well, it’s interesting, because you mentioned Midjourney, and I’m doing a lot of generative art as well. And there’s a new word that people are using, which is synthography. I don’t know if you’ve seen this. You know, like photography is pictures that you generate with the device and synthography is pictures that you’re generating with AI. And I was thinking about this with how writing might change using these tools.

Given that you are an editor and you see people’s work, how do you expect books to change with AI?

John: I think revision might become easier. Like, say you have a character and I tell them, like, you know what, this character’s dialogue is really flat on the page. Okay.

And they can go back to ChatGPT and be like, “Okay, well, here’s all the examples of this character’s dialogue in my novel. Take an excerpt from every time this character speaks and tweak it in one way.” Make it a little bit more slangy, or make her sound like she has an accent.

You can just give the character some dialogue, and then you can just take all those revised bits of dialogue and put them back into your novel. And suddenly, you’ve done a revision which could take a really, really long time and be tough to figure out, and it’s done pretty quickly.

Joanna: Yes, I mean, even incorporating the ideas like asking for twists. Like I’ve been saying, “Okay, so this is how I think this plot is going to go. Give me ten other ways that the characters could behave in this situation that would be plot twists.”

And it’s coming up with things that I haven’t thought of that are better ideas. Then I’m like, okay, cool, I’m going to use that idea instead of what was originally my idea, and that makes the book a lot more twisty, in this particular example.

I think having a co-pilot for ideas is also really powerful.

John: Yeah, yeah. I suggest something pretty similar to that, and I couch it in terms of like writer’s block. Say you’re stuck in the middle of your novel and you don’t know what to do.

Well, you could have ChatGPT summarize your novel up to that point or you can write a summary and then say, “Yeah, give me five different ways the story could develop from here. Make sure to add a plot twist and a surprise,” and something like that. Like you can direct like, alright, these are the type of narrative developments that I’m looking for, give me suggestions. Yeah, a couple of them are dodgy, but there’s almost always at least a few that you’re like, oooooh, that sounds interesting.

Joanna: Okay, well, we’re almost out of time. But you also had another blog post where you said, “When will AI start writing novels?”

And you’ve said, they will write novels, not great novels, but readable novels. I kind of disagree. I think that the quality of what we’re even seeing now with us driving is great. But again, you’re an editor—

Will you know if someone gives you a fully generated novel, or even one partially driven by a human?

Do you think you’ll know?

John: That’s a great question. I don’t think I will know. I don’t know. And remember, we’re right at the very beginning of this technology. I mean, think about in two years or three years, I really do think that AI will be able to put together an entire novel. What I mean by maybe not a great book is I mean, you know, there are some books that, geez, and I guess I am thinking of literary fiction, where it’s like the density of language and everything is quite astonishing.

I feel like what ChatGPT will be best at, and other AI programs will be best at, is looking at ones that are based on models, looking at books based on models, whether like plot models, or characterization models, and hitting all those plot points. I think that very soon we’re going to see entire books written by AI.

I think humans will act more as editors.

They’ll go through and be like, “Okay, look, AI. That one chapter didn’t work for whatever reason. Rewrite it.”

And so you’re giving feedback, you’re almost acting like a beta reader for the AI program, being like, redo this part, redo this part, let’s change the ending to this. But in general, the AI will be doing most of the heavy lifting of the sentence writing and the plot development and everything, and you’re just guiding it.

Joanna: It is interesting because I think people will choose the way they’ll create depending on how they’re feeling. So I definitely think you’ll do different things depending on what you want to achieve. And as humans, we still want to create. I think that’s the basic thing.

So people listening, you’ll still write how you want to write. We’re not saying that this is the way it has to be, but it’s another way to create.

In the same way that I love taking pictures with my iPhone, I’m not a painter, and I love using Midjourney. I don’t draw. I think as a writer, I still hand write in my journal, I still type on my laptop, I still dictate, and I use AI. So you can use all these things to create what you want. I guess that’s how I see it.

John: Yeah, I think a lot of writers aren’t going to use AI because they get a lot of pleasure out of doing it themselves. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with that. I mean, I get a lot of pleasure out of coming up with something out of my own brain rather than having AI do it for me.

That doesn’t mean you can’t still use AI as a great tool to help you with revision or to help you with idea generation, and then you actually do the writing of the sentences.

You just got to navigate those sorts of relationships for yourself.

What I don’t get is writers who are like, oh, like, I hate all AI. It’s like, well, do you use Microsoft Word? Like, there’s like spelling and grammar correction on there already. Like you’ve already been working as a hybrid author with technology for the last 20 or 30 years. This is just better software, so I don’t think you should hate it. You should use it to whatever extent that you want to use it.

Joanna: Fantastic.

Where can people find you, and your books, and your courses, and these blog posts online?

John: So you can Google Bookfox or the URL of my website is TheJohnFox.com. The name of my book is The Linchpin Writer which you can find on Amazon. All my courses are on my website. Then of course, I’m on socials. I’m mainly on TikTok, but also on Instagram and YouTube as well.

Joanna: Well, thanks so much for your time, John. That was great.

John: It was a pleasure talking with you, as always.

The post originally appeared on following source : Source link