Podcast: Download (Duration: 1:19:42 — 64.0MB)

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | TuneIn | RSS | More

Memoir can be one of the most challenging forms to write, but it can also be the most rewarding. Marion Roach Smith talks about facing your fears, as well as giving practical tips on structuring and writing your memoir.

In the intro, Amazon’s category changes [KDP Help; Kindlepreneur; Publisher Rocket]; Book description generation with AI; Thoughts on New Zealand and how the river forks; AI is about to turn book publishing upside down [Publishers Weekly]; Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable – Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

Plus, Japan and copyright for AI training; Microsoft rolls out Designer to Teams; Google Docs text generation with Bard [Ethan Mollick]; Photoshop and generative fill [NY Times]; Drug discovery with AI [BBC; Alpha Fold]; Amazon generative search job listing [Venture Beat]; ChatGPT official app; My webinars on using AI.

Today’s show is sponsored by Draft2Digital, where you can get free ebook formatting, free distribution to multiple stores, and a host of other benefits. Get your free Author Marketing Guide at draft2digital.com/penn

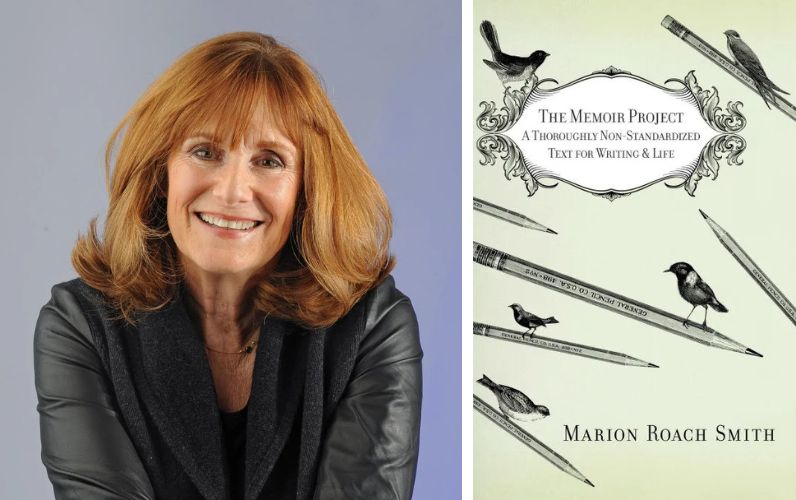

Marion Roach Smith is an author, memoir coach and teacher of memoir writing. She has online courses on writing memoir and hosts the Qwerty Podcast about memoir. Her books include The Memoir Project: A Thoroughly Non-Standardized Text for Writing & Life.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- Discovering what to shape your memoir around

- The writing process of memoir

- Deciding on the structure of your memoir

- The importance of the title to convey your book’s message

- Fears faced when writing memoir and how to overcome them

- How to know when your memoir is finished

- Traditional vs. indie for publishing your memoir

You can find Marion at MarionRoach.com

Transcript of Interview with Marion Roach

Joanna: Marion Roach Smith is an author, memoir coach and teacher of memoir writing. She has online courses on writing memoir and hosts the Qwerty Podcast about memoir. Her books include The Memoir Project: A Thoroughly Non-Standardized Text for Writing & Life. So welcome back to the show, Marion.

Marion: It’s a joy to be here, particularly to talk about your fabulous memoir. So I just want to get that in real fast.

Joanna: Thank you so much. You were last on the show, and we were talking about memoir, in July 2020. A lot has changed since then. So for those who don’t know you—

Tell us a bit more about you and your writing background, and why you are so passionate about memoir as a genre.

Marion: Well, I’ve learned that —

Memoir is the single greatest portal to self-discovery

— and I’ve learned that in my own career. I was a young New York Times employee when my mother got sick with a disease that no one understood, it’s now understood to be Alzheimer’s disease, and I wrote about it extensively.

After that, in the 40 years of my career since then, I’ve written a lot of pieces of memoir, all of which allow me to explore things that I didn’t actually understand when I sat down to write about them.

And I do understand them a bit better now. I genuinely now believe, having worked with people for almost 30 years on their memoir writing, that everybody benefits from it.

So I, in COVID, have had the great opportunity to meet a lot more people because a lot more people decided to write books, op eds, essays, long-form essays, and even just blog posts in COVID, and do a lot of exploration.

What I’ve witnessed has been really informative. So I think this introspection, this global introspection that we were plunged into, has resulted in a lot of good copy.

Yes, it’s been tragic. Absolutely. But your book is an example of the time taken after the plunge to see what we really think. I think that that is the best up-to-date I can give you, is that there’s good memoir out there, and there’s lots of it.

I’m teaching a lot of it. I did record all of my classes during COVID so people could have them on demand. That’s probably my news. But mostly my news is that I think that people have spent time thinking, and I’m deeply grateful for it.

Joanna: Yes, I did want to ask you about the pandemic. I mean, I wrote Pilgrimage in the pandemic. It did feel like that chance to pause.

And also, for me, it’s always this idea of memento mori, remember you will die. Is that a common thing with memoir? Not just with the pandemic, but in general, is it sort of confronting our mortality is why we almost want to write these things? I mean, with you, you mentioned with your mum, I mean, that was a mortality moment facing Alzheimer’s.

Is it fear of death or thoughts about death that makes a lot of people write?

Marion: Well, as you know, there’s nothing like a deadline, Joanna, and we all need them. I do best, literally, when the thing is due in two hours. I can whip it out better than if you give me two weeks.

So what COVID brought very clear to all of us is that we’re all on a deadline. I think that whether it was conscious or unconscious, the memento mori idea is positively motivating. I need to get this out.

And that’s what I saw was an astonishing amount of input worldwide from people. I did hear from people all over the world, and this is one of the few things we’ve shared is the global recognition that we’re all on a deadline.

Joanna: I’ll tell you one of the things that I have heard from people and that I felt myself is, well, but what does it matter?

When we sit down to write these things, will anyone care?

You know, there’s all this stuff going on in the world, should I write this? How do we get over that sense?

Marion: We share our humanity when we write memoir because this is not autobiography. This is not the Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday version of your life, which really, very few people should have to be exposed to.

I don’t want to read your date book. I want you to do the curation from your life, to show me your transcendent change, just the way you do in Pilgrimage, in your beautiful new memoir.

You show us what’s at stake in the beginning, that you’re discontent, that you’ve got a real issue that you would like to walk through.

We get to see that transcendent change as you generously pluck for us, from your total experience, just those scenes that we need to see, and to witness transcendent change. We’re not reading your book because of what you did — albeit three remarkable pilgrimages. We’re reading your book for what you did with it.

That’s what the humanity piece of memoir does so beautifully. It allows us to witness your transcendent change. Always a memoir writer should keep this in mind.

We are reading your book for our own feeding, our own ideas of transcendent change.

Your book gives us the sense that we can change, that we can evolve, that we can have a portal, walk through it, and come out with a new consideration of life. So people do care, written well like yours is, we change reading it.

Joanna: You talk about that transcendent change, and this is definitely something that I was struggling with the shape of the book, in terms of I had loads of material and I didn’t know what it was going to be.

So I had the notes from my walks, I thought maybe it was some travelogues, or some guide books, and then I had these essays about my travels. I thought this sort of bubbling up from the bottom up is what I was thinking, that somehow it would turn into something. But as you say around the change, I didn’t know that it might even be a memoir until I realized my own personal change from the beginning to the end of the process.

So can you give us some more examples of what that transcendent change might be? I mean, transcendent change seems life-changing or something massive, but it might be smaller things, too.

What are some things that people might find in their own lives to shape a memoir around?

Marion: It’s a great question, because it doesn’t have to be a bummer, it doesn’t have to be misery based, and it doesn’t have to be huge.

It can be an absolutely huge story set in a war where you have some effect on that, but more often than not, it’s the small stuff of life that changes us.

The recognition that I am going too fast, and that if I don’t learn to meditate, if I don’t learn to bring a little zen here, I am going to be that person who is trying every day to demand from others what they simply cannot give to me. So that small change.

If you’ve ever witnessed a type A person trying to learn to meditate, it’s torturous, right? Because what do they do? They buy all the meditation apps, and where do they listen to them? In their car while they’re driving. It’s like, no, that’s not going to work. And it makes for an amusing, but also universal, peace.

So you can learn to love a dog. You can learn to love a garden, that it came with a house that you just bought. I always say to people —

If you write from one of your areas of expertise at a time, you will never run out of things to write.

You will have a writing life if you say to yourself, what do I know after what I’ve been through with the caregiving of my mother? What do I know after raising twelve dogs? What do I know after going on three pilgrimages? What do I know after living in this world with a sick child?

Those are each separate pieces. They’re either blog posts, essays, op eds, long form essays, or books.

People can write 8-10 book-length memoirs in this lifetime if they write from one area of their expertise at a time, and stop writing that autobiography that begins with their great-great grandfather and ends with what they had for lunch today. That is a book you’re never going to finish because there’s always lunch tomorrow, and no one’s ever going to read.

So everything is memoir if you look at it from one area of your expertise at a time. How did you learn to accept your illness? How did you learn to love that dog that your sister insists you must care for while she goes off in the army and fights? But you know you don’t want that dog, and we know that your sister knows that you need that dog more than you need anything. Small stuff, areas of expertise, you will never run out of things to write.

Joanna: I love that. And yet, this is also the problem with me. I had like 100,000 words, and the final book is I think less than 30,000. I mean, it’s crazy.

There was a heck of a lot of writing that did not go in this book, and may never go anywhere.

So is that how it works for most people? Or what are the pieces that will go into this? Is it just a case of sitting down and writing it end to end, and I just did it wrong? How do people come at a memoir?

Marion: You did it absolutely right because you did curate so that the book moves. As soon as a reader knows something, they don’t need to be told it again.

In an alcoholism memoir, we don’t need 19 scenes in act one that show us that you have a drinking problem. Once you’ve established that with the reader, we now want to know what the drinking problem’s effects are.

Do you make bad decisions? If you make bad decisions, do they include people you hang out with? Like you can take it a few more steps, but I just don’t need to see 19 scenes of you in different bars. And you think ,oh no, but they’re different bars. No, the message is the same to the reader, “I have a drinking problem.” Now we need to see what choices you make after that, and then we need to get out of act one because now we want to know if you can sober up.

So you did beautifully curating, simply stating for us in your act one what the issue is, what the problem is. You use this beautiful German word, which I’ll probably mispronounce, but fernweh, the longing for far-off places. How do you pronounce that, by the way, Joanna?

Joanna: Yes, I mean, almost. Fernweh.

Marion: Fernweh. So you’ve got that combined with this collective grief that we’ve got, this global grief, and you stated definitively that you couldn’t control the pandemic, but you could walk out the door with your backpack.

That was a very good selection amid probably other things that are going on your in your life, which you said, well, we don’t need all of those. So you made this curated attempt. So you did do this perfectly. 100,000 words makes perfect sense to me.

I frequently say to people when I’m teaching memoir writing, first you have to pack a trunk, the kind of trunk you might take to camp for two months. Then we’re going to turn that trunk into an overnight bag, but I have to see the trunk to be able to select which sweaters are going to go with you and which are not.

Mostly people write big and then we sculpt it down after that.

I call it the vomit draft, that first draft, that 100,000-word behemoth.

And you know, you should treat it like a vomit draft. I mean, it’s going to be stinky, and it’s going to have everything in it that you threw up on this one topic. Then we get it down to the overnight bag. And you did that exactly right. I didn’t feel there was repetition. I felt as soon as I knew something you moved on. And that’s exactly your assignment as a memoir writer.

Joanna: It’s so interesting, though, because, I mean, this comes down to the editing process versus the writing process.

That introduction and the epilogue, they’re the last things that I really wrote, or I rewrote, and rewrote, and rewrote, until I did have a clear opening and closing to the arc of the character, which was me.

But coming back to how other people can write their memoir, I mean, you’ve been giving us questions.

So is it a case of just starting? I mean, you mentioned essays and things.

How do people get started with a memoir?

Should people start writing little essays or little journal pieces on things they’re thinking about? Or is it that they almost give themselves questions around various aspects? Or, for example, with your mother, is it journaling while someone is going through suffering and then looking at that later? How are people writing that main meat of what turns into the trunk?

Marion: Well, those are a couple of great questions that allow me to really reflect on what we’re doing here.

So first of all, your comment about how you wrote the intro and epilogue last, that is some of the best advice you can give to memoir writers. If you write your introduction first, you’re going to be forced to write the book to that. And you don’t even know what you know, until you write that big 100,000 word vomit draft.

You think you’re writing a book about mercy, and suddenly you’re writing a book that’s all about the particulate matter that goes into mercy. That’s a very different thing. So you want to wait till you’ve written a first draft to ever write your introduction and your epilogue. I just wanted to say that you did that exactly right.

In terms of starting out, in terms of are you going for the snippets that you have in your journal, or are you answering big questions, I would say that —

Memoir is always based on a question.

Can I sober up? Can I live in this world the way it is? Can I completely and absolutely love this child who is so ill and who is going to require my time in a massive way? How am I going to navigate with love and care through this experience?

So, frequently it begins with a question. Sometimes, however, it begins with keeping a journal on something.

You know, you just got a garden journal, or a knitting journal, or a journal of a caregiving experience, and you find that you really are quite interested in the process of your own change. So you go back and you look at those journal entries, and maybe you do start with a personal essay.

I genuinely believe that testing your material on the public is a great idea.

Op-eds, opinion pieces that appear in the newspaper, are great ways to attract the attention of an editor or an agent. They’re also great ways to hone your argument, and every piece of memoir is an argument.

What I mean by that, I don’t mean argumentative. I mean, it is a state for the record, stating for the record what I know after what I’ve been through, what you’re willing to share with someone.

So, frequently a piece will start with a recognition. “I think that dogs do things for people that people can’t do for themselves.” Oh, what an interesting place to write from. Or that closure is a myth, or that grief is a process that must be gone through slowly in order to go through it. If you rush it, you’re going to stay in it forever. I think I know that.

So you can start with a question, you can start with a conclusion, you can start short with an op ed or an essay, you can call from your journals, but you have the ability to enter this process anywhere along the line.

A small piece is a perfect place to start, as long as you don’t start with that intro or epilogue, because that will confine your work and curtail your discovery, and there’s lots of discovery of memoir.

Joanna: Yes, absolutely. And it’s interesting, you mentioned testing ideas there, and I started my second podcast, Books and Travel, in 2019 just before the pandemic.

It gave me a chance to do solo episodes around reflecting on various travels. They were essentially sort of mini-essays about various places I’ve traveled and the effects of those travels.

So I had originally thought that—talking about titles—the original title was Untethered, and it was about finding a home after traveling around the world.

Then I wrote and did the solo episodes, and it just didn’t hang together. This idea of how it hangs together, the structure of a memoir, I mean, Pilgrimage is both a journey, a sort of A to B journey, the moving across the world, but it’s also an emotional journey. There are other memoirs that are these sorts of essays within a theme.

What are your thoughts on trying to decide what the structure of a memoir should be and finding models in that way?

Then we’ll come back to titles.

Marion: So the structure of a memoir should always be taking an idea from here to there.

From when you could not do something to when you could. From when you did not know something to when you did. From when you had to shed something to when you shed it, and how life got better. Everyone takes on too much, just go from here to there.

So that’s your basic structure, and those are your bookends. From when I didn’t know something to when I did.

So what you want to do is to consider how would I best portray my here to there via my argument. Would it work to do it in shards? Little, tiny, half-a-page-each pieces. They’re not essays, they’re really like patches. And because I’m having a very disjointed experience with this problem, those might work. In other words, that might support the argument. These are just little ideas that I have about this very big problem I have. So that structure might really support the argument.

Essays sometimes support the argument best, a series of essays that still run from here to there. From what’s at stake, Act One, to what I tried, Act Two, to what worked, Act Three, is the way I think of the three acts.

The essay structure can work very well because they are self-contained. They allow the reader to sort of pop a lozenge in their mouth and let it melt and then pop another one in. That sometimes works for some arguments.

But in your case, and going from this, ‘what’s at stake’ all the way through, works beautifully with the narrative, the way you did it, combining the Pilgrimage workbook with it, giving us a sense that we’re learning along the way, including the references that you do.

It’s very well annotated, as it should be, because you’re backing it up with a lot of material about the places you’ve been.

Structure should be something that furthers the argument. What best furthers the argument? So, you know, little shards to essays to narrative length chapters that work, included with a workbook, it makes sense the way you structured it.

As to the title, I get why you started with Untethered, but you worked to Pilgrimage: Lessons Learned from Solo Walking Three Ancient Ways.

This tells us, the reader, the potential buyer, that there is going to be this exploration of pilgrimage, that there are lessons that are learned, that you did this alone, that you’re a woman, and that there’s an ancient aspect to it. The delivery on this title is excellent.

The title itself does a great job of pulling the reader in.

There’s something there for everyone.

So I think that you did a terrific job of moving from untethered, which you present in Act One as your problem, right? You are untethered. We get it, you needed to do something in this pilgrimage. Nobody goes on a pilgrimage lightly, I don’t think. So the untethered gets in there, but it just isn’t stated in the title.

Joanna: Let’s talk more about titles because it was really hard. I mean, originally it was Untethered: Travels in Search of a Home, which included a lot more about, for example, my mum taking us to Africa and moving to Australia and New Zealand, and none of that made it into the final book.

I mean, like you said, it actually does start with being untethered and finding a home by the end. So the whole thing is already there.

I’ve been writing 15 years now so I did think about keywords when I was doing my title. This is obviously difficult, especially if people are writing a memoir, it’s a very emotional topic.

[If you need help choosing keywords for your title and metadata, check out Publisher Rocket.]

What are your recommendations around deciding on a title and combining the keywords with the emotional side of things?

Marion: I love that you brought up keywords because we are selling a product.

And people get so emotional, they say, “Oh, my publisher is treating it like a like a widget.” Well, yeah, they are because they want to sell it. So we need to have some recognition of that.

When we’re choosing our title, it’s best to think about not being pretentious, and not being too literary, and not trying to communicate too much over the heads of the person who’s in the bookstore or online.

And instead, think about what are the reader is looking for. Not that you want to just always cater to your reader, but you want to consider your reader. This title allows us to know what the promise of the book is, which is deeply important.

I remember in my first book, I was 26 years old, I was with, at the time, the greatest editor in New York. I was so lucky. I actually fought with her to put a ridiculous title on my first book. I wanted a quote from Emily Dickinson because I loved Emily Dickinson, and I wanted to call the book The Hour of Lead. Now, let’s just be honest, that is terrible idea. What is that about, and you know, with some really esoteric subtitle because I wanted to be taken seriously. Well, that’s not my publisher’s problem. That’s my problem, right?

So don’t try to solve your problems and become, quote, “legit” with the title. Instead, what does the book cover? What does the book do? What is the promise in the subtitle of the return on investment for the reader if we read this?

I’m going to learn the lessons you learned solo walking three ancient ways. I’m also going to get this great exploration of what pilgrimage really is.

And I must tell you, I found myself deeply considering the idea of pilgrimage, even from my own armchair, and the transcendent change that happened. So I think that the title needs to be considered, but you absolutely don’t go over the heads of your reader.

Joanna: It is super difficult. So talking about one of the emotional sides of the process is fear.

I mean, I had so much fear in this process, mainly fear of judgment, which I always struggle with, about what people might think of me because of what I’ve written. There are some mental health issues in the book.

I guess I was just scared of what people would think of me and some things that I haven’t shared on this show, even though I podcasted throughout the last few years. So that’s my big fear — fear of judgment.

What kinds of fears do people face when writing memoir? What are your tips for overcoming them?

Marion: Well, memoir has consequences.

The consequences may be as simple as that you did not include your sister. And depending on your sister, she might not take that well. But if the story covers some period of time, and it’s about a transcendent change that isn’t, in fact, part of your story with her, then she doesn’t need to be in the book gratuitously.

So one of the first consequences is limiting the scope of a story. You may leave out your husband, you may leave out your parents, you may leave out your kids. So not everybody’s going to like that. That does obviously touch into judgment.

There can be consequences if you write about something that can be potentially litigious or actionable. In other words, in abuse memoir, we have lots of experience with people who change their name, change the name of the people.

I always recommend that you don’t just change the names, but you find a more literary way. Give the people diagnoses, you know, maybe call the person the abuser, call your mother the complicit one, call your father the deaf who didn’t hear your pleas. Think about ways to do this. And I don’t give legal advice ever, but at least get the story on the page before you change your mind about writing it, and change the names to something that’s a bit more literary.

But there’s all this fear, right?

Fear of judgment and doubt keep a lot of people from writing.

So what I always say to them is, there’s so many reasons not to write. There’s kids and houses and jobs and dogs that need to go to the vet. Let’s take fear off the table.

And let’s do that by getting involved with maybe one, or a small group of people, who are invested in your success. In other words, in a writing group, with a writing coach, with a developmental editor, with a one-on-one person, so that you can just not tell anybody else that you’re doing it, not tell the family that you’re doing it, get the job done, and let’s see what you’ve got.

Then when you’re going to take it to market, there will be fear of judgment. You were very transparent here. You talked about your failed first marriage, you talked about your mental health, you didn’t tell us everything, but we don’t need everything.

And what you did instead of us judging you, was you allowed us to be with you. You allowed the kind of transparency that makes us feel that we’re sitting together next to each other having a talk, as opposed to you preaching to us which I cannot tolerate, or being really dogmatic, which I cannot tolerate in a narrator.

So the fear, we should try to take it off the table by through several devices. Certainly changing the names if you need to do that. Certainly writing to only a very small audience that accepts and is invested in your success. And then the fear of publication and the fear of rejection is going to be there, you are, after all, taking something to the market.

Here’s the deal, you need to bring the best possible writing to this because this is a book, and it will be judged by its writing.

So if you bring the best possible writing, you tell the truth, you make a product that you can live with and standby, you’re doing what writers do every day, which is contributing to a conversation that we all need to have. So maybe you can raise your sights knowing that you’re doing this good thing and contributing to some major conversation and it’ll blow past some of that fear.

Joanna: Yes, because I guess there’s the fear of writing, itself. Even when it’s just you on your own, and the people who have deep trauma to get through, there is fear of just bringing that even to the page, versus the fear of putting it out in the world when other people will see it and potentially read it. Although perhaps not as many people read these things as we would kind of like, as well.

Marion: Well, the deep trauma thing is a very good point. I’m glad you brought that up. Because what are we asking a memoir writer to do when we ask her to go and write about a past trauma? Are we asking her to reanimate it? Are we asking her to relive it? Are we asking her to stand coolly back from it and have a look from some distance? And every memoir writer will answer that question differently. I’ve asked every memoir writer that I’ve interviewed on my podcast that question, and they all have different answers for it.

I believe my own answer to that question is I’m not asking you to relive it. If it is a trauma, you probably should have some kind of counseling while you’re writing it because any number of things could come up.

What we’re looking for you to do, is to tell us the truth and to show us the transcendent change.

So right in there is a key to how to get this done. You get to choose how the story goes from here, and that is not something that maybe you got to choose before if you are the victim of some trauma. Maybe it’s been told to you, maybe it’s been labeled in a certain way. Now you get to get your hands on your own story. I hope that the invitation of that allows people to enter it.

I’m not saying you get to make up an ending, but you do now get to choose when this thing is over. That’s a very powerful thing.

I’ve noticed it with a lot of MeToo memoir that I’ve handled is that people get their voice back. One of the things that’s taken when someone violates the territory of your body is your voice. So to get your voice back, I have been happily reduced to tears, constantly, over the last five, six years, editing MeToo memoir, watching people get their voices back. So my invitation to everyone is —

Use your voice. You’ll be astonished at what it’ll do for your life.

Joanna: It is a very powerful process to write this and understand — like you mentioned, at the beginning, it’s a portal to self-discovery.

But one of the big questions is really when is a memoir finished, in terms of when is the book finished?

I felt I understood when it was, it was when I returned from my Camino de Santiago and I realized that I’d come home, and it was like I’ve been through the character arc. But it was only once I’d been through the character arc that I realized it, and then I could write the memoir. So is that the feeling that everybody gets?

How do you know when the book is finished?

Marion: I think there’s a variety of feelings that people get.

And some people, you know, when I wrote my first book, there used to be these things called safe deposit boxes that you had at banks where you kept your valuables locked up. And I used to go down, this is true, to the bank every day with my pages and put them in the safe deposit box. Less, you know, my apartment buildings should burn down. But it was the day that I got to carry them all home when I was finished.

I’ll never forget walking up Columbus Avenue in Manhattan, carrying my, whatever it was, first draft, 325 pages, and holding it to my heart and knowing that I had something. Nothing in this earth has ever quite come close to that first feeling.

But when is a memoir finished? Well, a memoir is finished when you’ve proved your argument. And this is a really important thing to remember, many, many, many memoirs will be finished 15 years ago, in terms of the chronology of your own life. It’ll be done when you did experience that transcendent change and you can show us the proof of that.

Yours, you wrote right on the heels of an experience, almost writing it in real-time. But it’s still done when you’ve proved your argument. It’s still done when you’ve discovered what you’ve discovered about home. You’re still done. So you can move on to your next book. So it’s done when you’ve proved your argument.

Joanna: I was just imagining you walking along the street thinking, oh, my goodness, don’t get mugged or fall over I drop it, or I mean, that just seems crazy now!

Like everyone — backup your work in multiple places, email it to yourself. That’s terrifying.

But yes, in terms of just the size, because that book that you mentioned, that’s a lot bigger. I did notice with mine, I mean, I’m quite happy with the length, but there was a point where I thought this should be longer, like this should have more in it.

Is there a length that people should be aiming for in terms of word count?

Marion: So it used to be that the rule was don’t even think of handing something into an American publisher anything under 75,000 words. Happily, that’s no longer the case. There are still old-time editors who like to have the heft of a book, but what I’ve seen, especially in this generation of younger writers, is much shorter copy. I think it’s the Twitter influence. I think it’s a lot of this social media influence.

I think that the people who write miniatures in America, we have people like Lydia Davis, and people like Abigail Thomas, who have written books that have very short, sometimes half a page is a chapter. So there’s the exploration of that that’s really warranted. So I encourage people not to set a word count in their own minds and hearts. That doesn’t mean that you’re not going to run into an agent or an editor along the way who says it’s too short.

I don’t feel that your book was too short, I felt that your book was digestible and it happened right in the timeframe it should happen, and it was the right length. But you really, really, really want to, again, prove your argument and see what form fits that argument best. It might be shards, might be short chapters, it might be long narrative chapters. But I worry less about word count these days than I used to.

Joanna: Well, you’ve mentioned editors and publishers a number of times. And I mean, I’m an independent author, so I was always going to go the indie route for this.

I know memoir writers who have traditionally published and who have chosen to go indie because of the control aspect of such a personal project.

What are the pros and cons of choosing a particular publishing direction for a memoir?

Marion: I’m so glad you brought that up, because yes, of course, you’ve always been indie, and I’ve always so admired that about you. You do a great job with it.

I think this is the greatest time in the history of writing for writers because there are choices. There’s independent publishing, which we no longer call self-publishing, thank goodness. It is independent publishing, meaning you have total control.

You can design the cover, you can make typeface decisions. I mean, I’ve seen brilliant typeface things these days, you know, in typography, but also how the layout appears on the page. Including a recipe, or including a poem, or including a picture, you have so much more control over what the book looks like. You also have control over how the book is distributed and where it’s distributed. I think for those people who are entrepreneurial, this is the absolute way to go.

This hybrid publishing, which is a mash-up between the two, where you put some money into it, and you also get the benefit of the distributor of the publisher. We have a bunch of them now. Well, we have more than a bunch, we have so many of them proliferating in the United States.

Then there’s traditional publishing. In the US, that means only the Big Four, which they’re referred to, that everybody knows. There are advantages and disadvantages. You have to keep in mind that with traditional publishing, the liability is entirely on the publisher, so they want their money’s worth.

If they gave you an advance, if they’re going to incur the entire cost, they’re also going to extract the most amount of money per book until you ever see any money, if you do, in royalties.

In hybrid, you get royalties faster. And an indie, you’re in control of the money. So depending on what kind of person you are, I think that you’ve got options. The only thing is I always say to people is do not think because you’re going with quote, “traditional publishing,” that you’re going to get a big advertising and tour budget. Those days are long over for almost 99% of the writers.

You’re still going to have to do the promo yourself, meaning writing those letters out to magazine publishers, or online places that you can publish. You’re going to do all that work yourself, you are. So if you’re going to do it anyway, why not indie publishing? So I think this is a great choice. It depends on the person.

Joanna: I mean, if people do want a traditional publisher, I mean, the sort of famous one in my head is Wild by Cheryl Strayed, which sold a gazillion, or I guess, Eat, Pray, Love was another famous one that got made into a movie. So people think, oh, if I just get a publisher then that’s what will happen to me. I mean—

Are traditional publishers even looking for memoir now?

It just seems, unless you’re famous already, that it’s difficult in that way.

Marion: Yeah, I still see lots of book sales. I’ve got 70-something books on my shelf of people that have worked with me who have published, and they’ve published in these various realms, indie, hybrid, and traditional. So I know it’s possible.

I just had on the podcast, somebody who actually lives in the UK, it was her first memoir, and she sold it, and she sold it big. She sold to a big publisher and got a big, wonderful advertising campaign for her book.

So I think I’m pretty sure that it’s going to be the value of the writing, and that’s what’s going to sell it. I do not see any diminution of memoir sales in this country. I’m getting approached by publishers every day with huge lists of memoir to have on my podcast. I think that you’ve got to study the market and understand the territory, but then you’ve got to do the best writing you can possibly do to sell a book.

Joanna: Maybe it’s also about the topic or the question, as you’ve mentioned, underlying the story. So I remember it was back in the 90s, it was ‘mis-mem,’ the misery memoir, where there was a lot of like abused children type of memoirs. Then like you’ve mentioned MeToo, and that, I guess we’re still in that moment.

There are also different themes that I guess come up when people tackle that in a memoir.

Obviously, we’re not going to write something to market with a memoir, but perhaps that also has an impact on whether publishers are interested.

Marion: I think so. I mean, it’s the job of a writer to understand what’s coming in the ether. That’s just true, right?

Writers react, that’s our job. And that is the first piece of information I give to writers. Writers react. You are supposed to be reacting, in essays, op eds, long form essays and books, reacting to what’s going on in the world, what’s in the ether.

So the question was at the beginning of COVID, are we going to want to read books coming out of COVID? Are we going to want to read a COVID diary of someone else? Or are we going to leave this whole thing behind?

Well, interestingly, yesterday, and this kind of timestamps this, but let’s just say recently then, the Pulitzer Prizes for fiction went out in the United States and a book that is absolutely a bummer, but is a wonderful bummer, their retelling of a Dickens story, won the Pulitzer Prize. It is positively and absolutely not a book that you don’t have to work through. It isn’t just joyous. So that’s interesting to me.

In other words, the public’s appetite for a bit of misery is still very rich and very accepting even though we’ve all been through three years of misery. We didn’t just emerge saying, I only want to read happy stuff, that’s it, no more bummer. Well, so we have to respond, right? Writers respond, and writers react.

So think about what it is that we might be interested in at the time that you can get this book published, to some degree, to some degree. That doesn’t mean you write entirely to the market, but what will be talking about? What will we be thinking about? That, I think, is your greatest consideration in terms of the outside market.

Then you’ve got to remember, and I say this to the writers I work with every day —

You better love the work because there is no controlling the market.

Things happen in the world. I have so many friends who had books coming out in the spring of 2020 whose books never saw the light of day because COVID stopped the distribution of books. That does happen. So try to love the work every day, because you don’t know what the market will bear.

Joanna: Absolutely. And I guess circling right back to the beginning, it’s well worth it to write a memoir. I mean, it’s crazy. This has taken me longer than any of my other books, and yet it’s shorter, and yet it feels like it was three years or more of my life. And yet, it’s so worth it.

It doesn’t really matter about the sales, it’s a brilliant project to do anyway.

Marion: I think it is.

I think that the great writers of the world, the Virginia Woolf, Zora Neale Thurston, Emily Dickinson, whoever you love, James Baldwin, Charles Dickens, they’re the Amazon. But we are the tributaries, we are contributing, we are definitely trickling into the conversation.

So write. Contribute to the conversation. We share our humanity in memoir, and it is absolutely life-affirming, and I believe in it with all of my heart.

Joanna: Brilliant.

Where can people find you, your books and courses, and your podcast online?

Marion: How kind of you to ask. I’m at MarionRoach.com. That’s where the Qwerty Podcast is housed. I run the transcripts of it. It’s also everywhere podcasts are available.

The books and everything else are available at MarionRoach.com. It’s just a joy to talk to you, Joanna. I’m just delighted. And the book is wonderful, so I hope you sell a billion copies of it.

Joanna: Well, thanks so much for your time, Marion. That was great.

Marion: You’re welcome. Be well. Talk to you again soon.

The post originally appeared on following source : Source link